When traditional approaches confound, CRISPR-Cas9 provides clarity by editing the cell’s own protein blueprint.

In this blog, Dr Phil Auckland details how MDC has established a reproducible CRISPR-Cas9 pipeline and generated new tools to better inform nanotherapeutic design

December, 2025

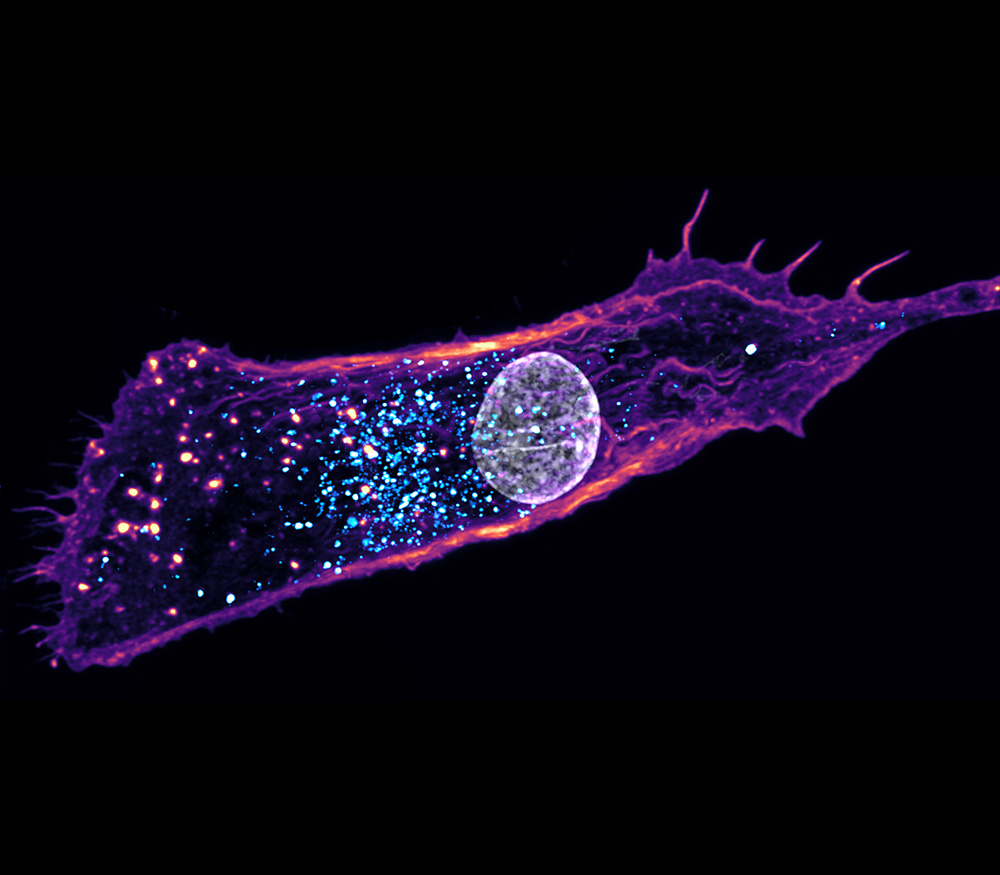

Human cell models offer a flexible and biologically relevant way to study mechanisms of disease pathology and to evaluate how potential therapies work. The analysis of living cells in real-time allows researchers to observe biological processes in unique microscopic detail that isn’t possible with other experimental systems. This makes cell-based experiments a key part of modern drug discovery.

The need to find novel therapies for disease is driving the development of new and translationally relevant cellular models to guide drug development and enhance clinical success. The importance of this is underscored by the FDA’s plan to phase out some animal testing requirements for many drug modalities, and reduce and refine these studies where possible. With other governments set to follow, developers are now increasingly focused on building cellular models that accurately capture the biology of health and disease. While in vitro model adoption throughout the drug discovery pipeline will be influenced by clinical applicability and translational validation, the potential for human model systems to enhance drug discovery research is becoming increasingly apparent.

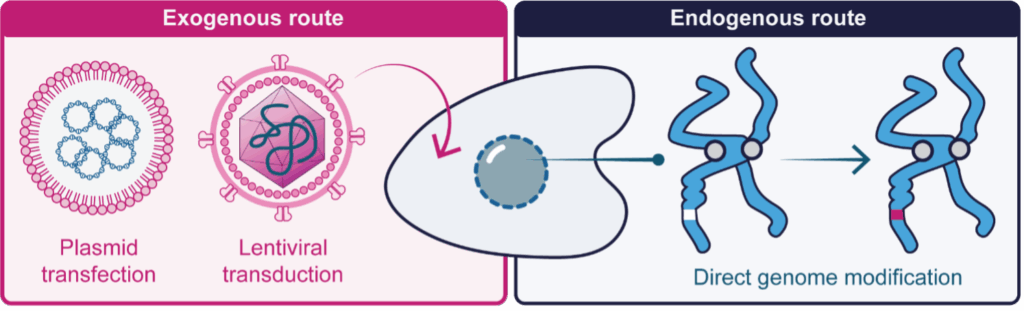

Building a cellular model to recapitulate disease biology often requires protein modification, such as manipulation of a disease-associated protein or the labelling of a pathway or compartment reporter. The conventional approach has been to introduce the modified protein into cells (exogenous expression), where DNA, encoding the altered molecule, is delivered to cells in lentiviral or plasmid form (Figure 1). Such methods often drive high protein production, generally many-fold more than a cell could make via nonsynthetic means, and are therefore referred to as overexpression studies. While the abundance of modified protein simplifies experimentation, it can alter the stoichiometry and therefore function of cellular systems, and as a result, be less representative of the biology in question.

The alternative to exogenous expression is direct modification of a cells own DNA genome, leading to production of an engineered protein under the control of normal cellular processes (Figure 1). This endogenous route is well-understood to be the ‘gold standard’ method for generating cellular models, as the level of protein expression is conrtrolled and biologically relevant.

Figure 1: Methods to modify a protein in living cells. Left The exogenous route, where DNA encoding the protein of interest is synthesised in a laborotory and introduced to cells via plasmid transfection or lentiviral transduction. This yields a large amount of protein and is referred to as overexpression. Right The endogenous route, where the cells own DNA genome is stably modified to produce a modified protein under the control of normal cellular processes.

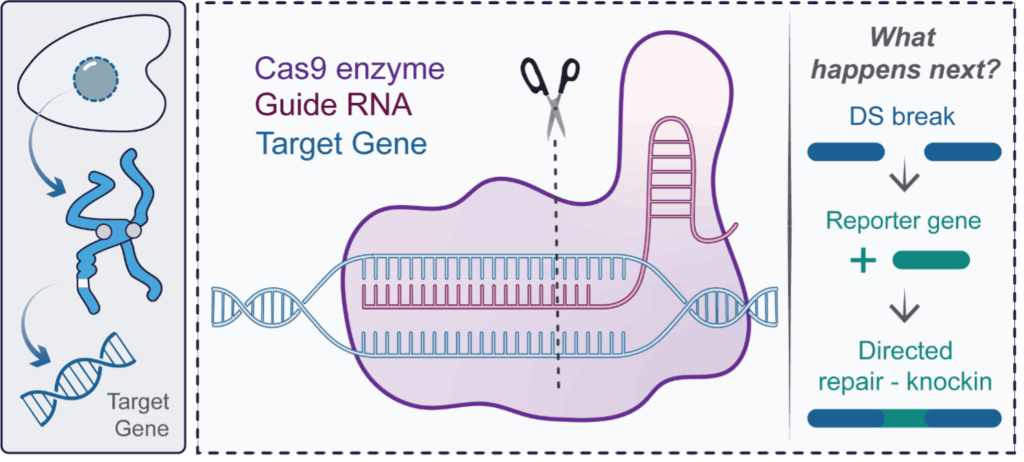

Despite the utility of endogenous protein engineering, the approach was traditionally limited to select laboratories due to its reliance on complex methods such as zinc finger nucleases and TALENs. In 2012, a shift in this paradigm was initiated by the publication of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR) -Cas9 genome engineering, which provides a more accessible method of endogenous gene expression and has transformed cell biology throughout academia and industry alike. In CRISPR-Cas9 studies, a modified bacterial enzyme called Cas9, is directed to a specific genomic region by a programmable guide RNA (gRNA) molecule. Cas9 is a molecular scissor, which following gRNA engagement and binding to the target genomic region, cuts the DNA across both strands to create a double strand break (Figure 2). The double strand break opens this genomic region to experimental modification, such as the insertion of new DNA provided to the cells at the time of Cas9-mediated cutting. For example, by programming Cas9 to cut at the start of a gene, a gene encoding a fluorescent reporter can be inserted (from here referred to as knockin) with the consequence being that the target protein is tagged and can be visualised with fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2). In recognition of its widespread and revolutionary impact, the inventors of CRISPR-Cas9 were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Figure 2: An introduction to CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering. In CRISPR-Cas9, a modified bacterial enzyme called Cas9 is directed to a specific genomic region by a programmable guide RNA (gRNA) molecule Cas9 is a molecular scissor, which following gRNA engagement and binding to the target genomic region, cuts the DNA across both strands to create a double strand break. This double strand break can be used to insert a reporter gene at a specified location, leading to the permanent production of labelled protein molecules. This process is termed knockin.

Nanomedicines span many cutting-edge therapeutic modalities. Most notable are mRNA-transporting lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), which include the Moderna Spikevax and Pfizer-BioNTech Comirnaty COVID-19 vaccines administered to much of the world’s population.

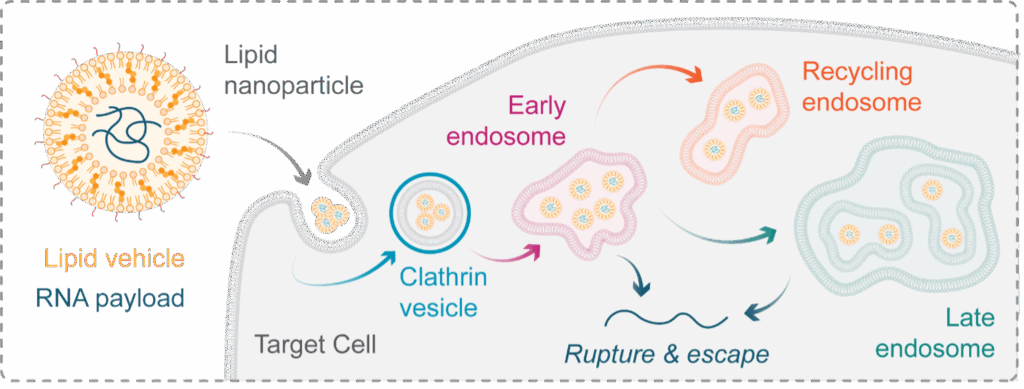

Once internalised into a target cell, LNPs traffic through a convoluted vesicular network known as the endolysosomal system (Figure 3). How LNPs interact with this network and how this directs therapeutic efficacy are largely unknown. To expand the therapeutic potential of LNPs the understanding of these processes at the mechanistic level is critical to guide structure-based design of novel formulations. However, it has been shown that mechanistic analysis can be complicated by the over expression issue described above; whereby overexpressed markers of endosomal compartments alter the physical and chemical properties of the respective organelles – indicating the need for physiologically relevant expression levels.

Figure 3: Lipid nanoparticles & the endolysosomal system. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are a therapeutic class capable of transporting RNA into a cell – a feature that holds significant promise for the future of genomic medicine. Once internalised into a tagret cell, LNPs transit a compartmentalised network known as the endolysosomal system. This system is made of distinct membrane-bound compartments, which determine the fate of material internaised into a cell. For LNP research we can simplify the network to early, late, and recycling endosomes, each with a unique protein identity. To function, LNPs must escape from these compartments into the cytosol by inducing their rupture, but the precise mechanisms governing this essential event are poorly understood, limiting out ability to improve the particles efficacy.

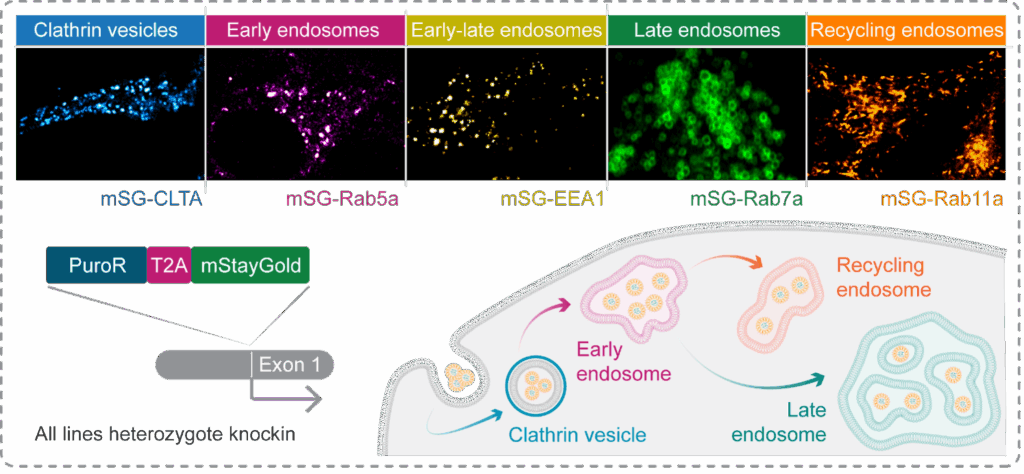

To build the first commercially available knockin reporters of endosomal trafficking, which overcome overexpression caveats, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to attach a fluorescent tag, mStayGold, to five proteins. These proteins signpost critical nodes along the endosomal pathway, such as early, late, and recycling endosomes (Figure 4). Specifically, in this example and as a proof of concept, HeLa cells were transfected with Cas9-gRNA complexes and a PCR-amplified donor containing puromycin resistance and mStayGold genes separated by a T2A site and flanked by homology arms (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Using CRISPR-Cas9 to generate knockin reporters of endocytic trafficking. To enable the visualisation of distinct endocytic compartments, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to knockin a fluorescent tag, mStayGold, at the genes encoding markers of early, late, and recycling endosomes, as-well-as clathrin vesicles. Cells were enriched via puromycin selection then FACS, and sucessful labelling confirmed by live cell imaging.

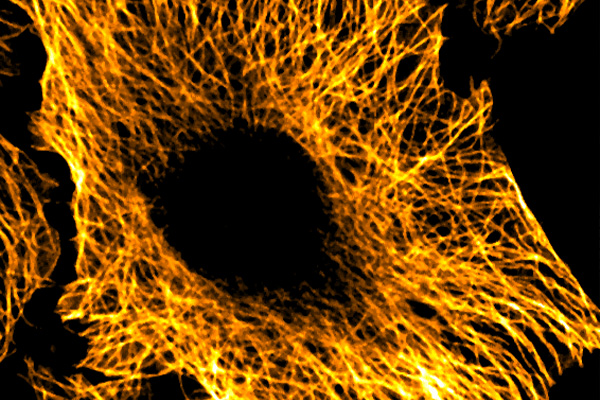

High-resolution live-cell imaging demonstrates successful knockin of the fluorescent tag, with each target protein revealing a differentially shaped and dynamic compartment that can be tracked in space and time (Figure 4). These tools allowed us to observe strikingly different phenotypes between the compartments. For example, Rab11a, which binds to endosomes along the recycling pathway, shows elongated structures enriched at the cell periphery and centrosome that rapidly traverse the cell in the order of seconds (Figure 5a & Movie 1). In contrast, Rab7a, which binds late endosomes prior to fusion with a lysosome, identifies large, relatively static spherical compartments in the perinuclear region (Figure 5b & Movie 2). The bright and highly stable mStayGold tag permits prolonged visualisation of these compartments without detectable bleaching or toxicity, confirming their utility for tracking the intracellular fate of nanotherapeutics. Altogether, this work has established a reproducible CRISPR-Cas9 pipeline at Medicines Discovery Catapult and generated new tools to better inform nanotherapeutic design – in line with our organisational commitment to enable breakthroughs that improve patient lives.

Figure 5: Tracking endosomes with CRISPR-Cas9-generated tools. (a) Top Stills of HeLa cells expressing endogenously labelled mStayGold-Rab11a, a marker of recycling endosomes. Note the elongated nature of these vesicles and their localisation to the centrosome and cell periphery. Below Time-lapse stills of a migrating mStayGold-Rab11a positive endosome taken from the white box above, demonstrating rapid cytosolic transport over six seconds. (b) Still of a HeLa cell expressing endogenously labelled mStayGold-Rab7a, a marker of late endosomes. Note the perinuclear localisation of these large organelles with a clearly visible lumen. (1) and (2) are zooms of individual mStayGold-Rab7a positive endosomes.

It is well established that endosomal trafficking and resulting entrapment drives attrition in LNP development. With these validated imaging tools, MDC can now track endosomal trafficking in real time to test how formulation influences the processes that underpin efficacy at the cellular level. This capability will not only clarify fundamental aspects of LNP biology but also empower developers to fine-tune their delivery systems to realise the vast promise of this therapeutic modality.

To learn about how we use these tools to advance LNP therapeutics, see our Rupturing Endosomes are not Created Equal blog.

If you are developing nanotherapeutics, speak to us about how we can make your next move count.

Find out more about how we can help

This is the first in a series of radiopharmaceutical blogs from Dr Juliana Maynard. Juliana is an expert imaging scientist with over 20 years’ experience in nuclear medicine and translational imaging.

Nanotherapeutics often fail because of Endosomal entrapment. In this blog by Dr Phil Auckland, we explore how MDC are using real-time imaging to reveal why.

Accelerating analgesic development through human-specific in vitro systems