Nanotherapeutics often fail because of Endosomal entrapment. In this blog by Dr Phil Auckland, we explore how MDC are using real-time imaging to reveal why.

December, 2025

We are in a new era of therapeutic development, where innovation is driving approaches to pursue previously considered ‘undruggable’ through new therapeutic approaches and the development of novel drug classes. The undruggable nature of many targets is due to the traditionally limited therapeutic toolbox available to medicines developers. Small molecule therapeutics have advantages in their ability to, enter cells, and bind deep pockets on their target protein. Conversely, monoclonal antibodies, can bind to target proteins either in circulation or on the surface of cells. However, many disease-associated proteins features that limit the utility of these medicines, including the absence of a binding pocket, the lack of an active site that drives function, or sequestration within a subcellular compartment; and any of these factors can render these targets undraggable.

Across decades of research, medicines developers have pursued a wide range of solutions, though the success has been varied. One of the most prominent successes in recent times has been RNA-transporting lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), which include the Moderna Spikevax and Pfizer-BioNTech Comirnaty mRNA COVID-19 vaccines administered to much of the world’s population, and Alnylam’s Onpattro siRNA for hereditary amyloidosis.

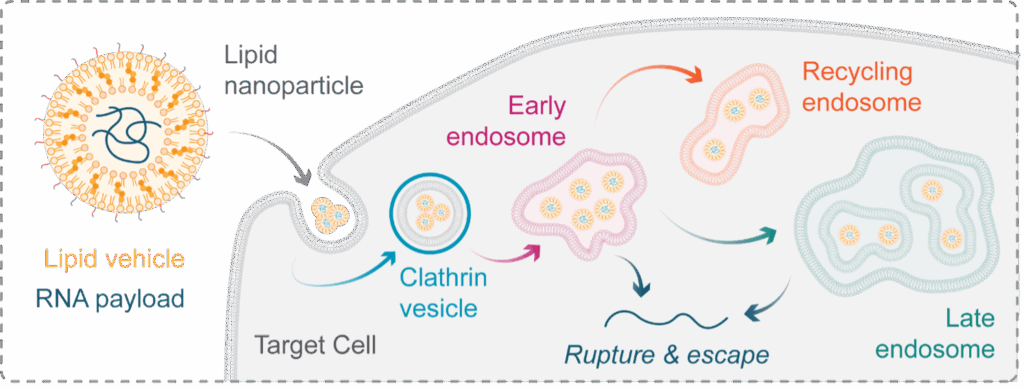

LNPs encapsulate an RNA payload, protecting it from damaging biological interactions and facilitating its transport into target cells (Figure 1). Their potential extends far beyond vaccines for infectious agents because the therapeutics utilise cellular processes translating mRNA into protein. Therefore, this therapeutic modality has the potential to cure genetic disease, enable personalised cancer vaccination, and license new targets in oncology by exploiting cellular biology and instructing target cells to produce, or modulate the production of, a protein of interest.

Once internalised into a target cell, LNPs traffic through a dynamic and convoluted vesicular network known as the endolysosomal system. This network consists of membrane-bound compartments called endosomes that transport internalised material throughout the cell. For LNP delivery we can simplify this system into three classes: early, late, and recycling endosomes (Figure 1), each with a unique protein identity that can be exploited for fluorescence labelling.

This internalisation route comes with a challenge: endocytic entrapment. For an LNP to be effective, the RNA payload must escape the endosome and engage with its cytosolic target. This is facilitated by the formulation of LNPs with ionisable lipids that, in the acidic environment of the endosome, create holes which the RNA can escape through. This is termed rupture and is essential for LNP function. Nonetheless, rupture is strikingly inefficient, with only 1-2% of internalised material reaching its site of action in the cytosol. Improving the efficiency of rupture in terms of RNA delivery is therefore a major aim for therapeutic developers.

Figure 1: Lipid nanoparticles & the endolysosomal system. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are a therapeutic class capable of transporting RNA into a cell – a feature that holds significant promise for the future of genomic medicine. Once internalised into a tagret cell, LNPs transit a compartmentalised network known as the endolysosomal system. This system is made of distinct membrane-bound compartments, which determine the fate of material internaised into a cell. For LNP research we can simplify the network to early, late, and recycling endosomes, each with a unique protein identity. To function, LNPs must escape from these compartments into the cytosol by inducing their rupture, but the precise mechanisms governing this essential event are poorly understood, limiting out ability to improve the particles efficacy.

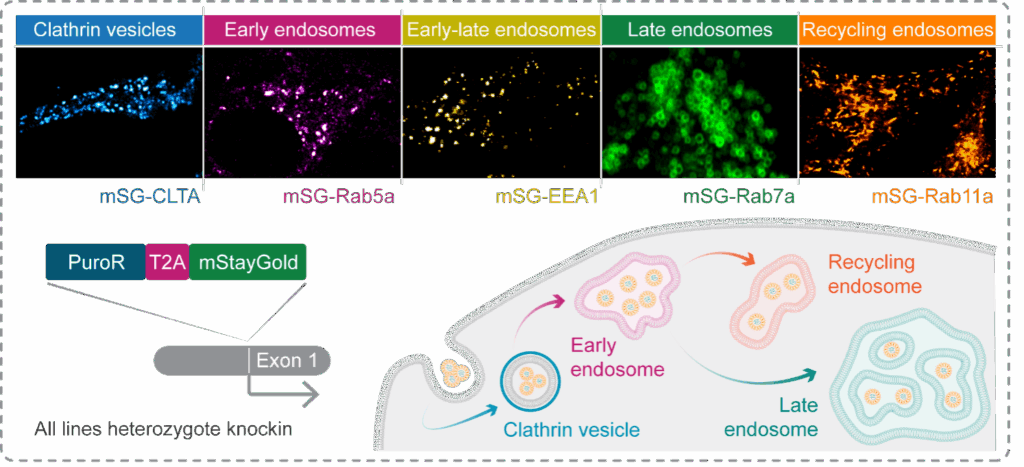

To understand how endosome identity governs rupture and cytosolic payload delivery, the process must be visualised in real time in living cells. To address this challenge, at MDC we have used CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering to knockin a fluorescent tag, mStayGold, to tag genes encoding Rab5a, Rab11a, and Rab7a proteins. This allows the dynamics of early, recycling, and late endosomes to be followed, respectively, using fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Generating a labelled endosome toolkit with CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering. To enable the visualisation of distinct endocytic compartments in live cells, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to knockin a fluorescent tag, mStayGold, at the genes encoding markers of early, late, and recycling endosomes, as-well-as clathrin vesicles. Cells were enriched via puromycin selection then FACS, and sucessful labelling confirmed by live cell imaging.

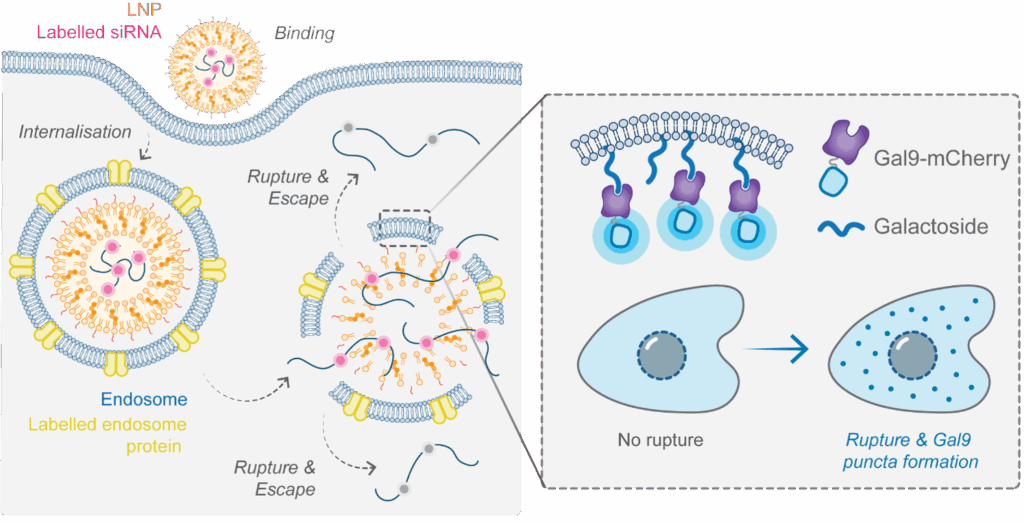

But this is only part of the process. To visualise the moment of endosomal rupture, we further engineered these cells to express a fluorescently labelled rupture sensor called Galectin 9 (Gal9). When an endosome ruptures, Gal9-mCherry in the cytosol rapidly diffuses into the compromised compartment and binds to specialised lipids on its interior, creating a fluorescent spot that can be imaged and quantified. Finally, to validate the cell reporters, we treated these cells with LNPs containing a fluorescent siRNA payload (Figure 3). With this toolkit, we could follow endosomal trafficking, rupture, and payload fate with high-resolution multiplexed live-cell imaging.

Figure 3: A multiplexed assay for LNP trafficking and endosomal rupture. To understand the interplay between endosome identity, LNP-induced endosome rupture, and payload escape, we established a multiplexed assay that combines endogenously labelled endosomes with an overexpresseed Gal9-mCherry rupture sensor and LNPs formulated with fluorescent siRNA-AF647. LNP internalisation is identified when a new siRNA-AF647 puncta appears in the cytosol. Three parameters are then tracked to determine the mechanistic fate of this paylaod. First, we use the endogenously labelled endosomes to determine what compartment the LNP has entered. Second, we use the Gal9-mCherry rupture sensor to determine the point at which the LNP induces the formation of holes in the endosomal membrane. Third, we follow the fate of the siRNA-AF647 payload after rupture, determining if it is released from the endosome into the cytosol, which is visualised as a loss of siRNA-AF647 signal from within the endosome. The siRNA-AF647 payload cannot be visualised in the cytosol as the molecules are too diffuse and therefore fluorescence cannot be detected above background.

Endosomes mature following their formation, transitioning from an early to late state over time. This poses a key question: does the timing of rupture relative to endosome maturity influence whether the payload successfully escapes?

First, we confirmed the rupture sensor was a sensitive readout of endosomal disruption and payload escape at the single endosome level. Consistent with the model shown in Figure 3, a single endosome containing LNP-siRNA-647 could be tracked as it formed, trafficked through the cell, then ruptured (Figure 4a). Furthermore, we found Gal9-detected rupture led to payload escape, as evidenced by loss of siRNA-AF647 signal immediately following Gal9 localisation (Figure 4b).

Figure 4: Tracking rupture at the single endosome level. (a) Movie stills of a HeLa cell expressing the Gal9-mCherry rupture sensor transfected with an LNP encapsulating siRNA-AF647. This assay enables the LNP-siRNA-AF647 complex to to tracked as it transfects the cell, enters an endosome, traffics within the endosome, then induces rupture (determined as the point of Gal9-mCherry recruitment). (b) Left Movie stills of an endosome conatining an LNP-siRNA-AF647 complex undergong rupture and releasing the siRNA-AF647 payload (determined as the point of siRNA-AF647 signal loss). Right Quantification of the reciprocal relationship between siRNA-AF647 and Gal9-mCherry signals as an endosome ruptures and the LNP payload escapes into the cytosol.

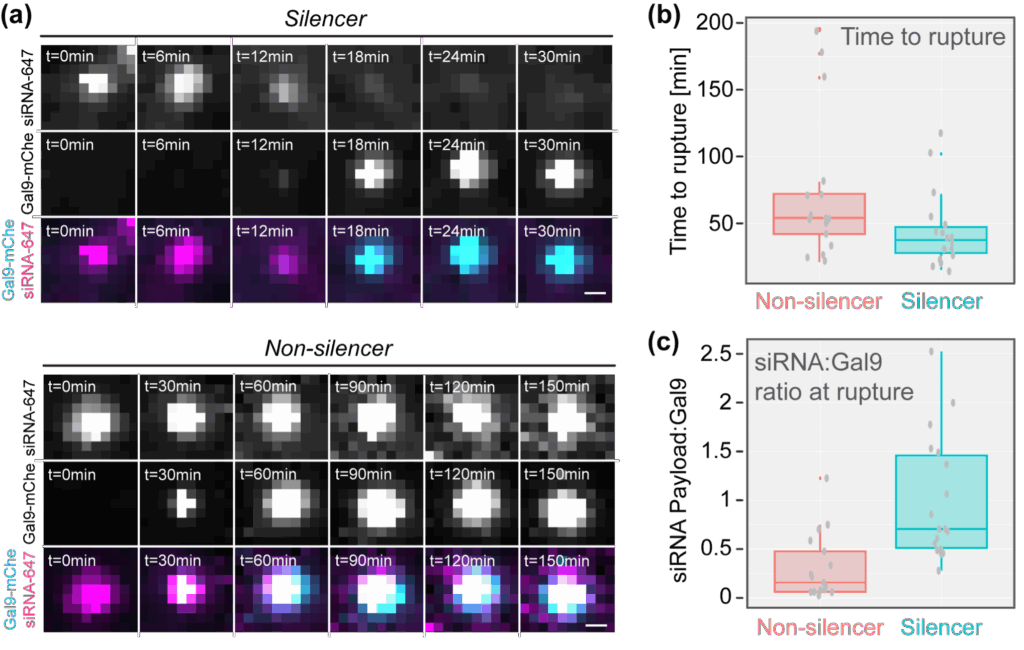

While common, this rupture-escape relationship was not entirely conserved. Instead, we found that endosome rupture can be categorised into at least two groups; first, rupture that leads to loss of the siRNA signal, indicating payload escape, and second, rupture that does not – where rupture happens but the signal remains. We termed these productive and nonproductive events “silencers” and “non-silencers”, respectively (Figure 5a). Quantification revealed that silencers ruptured more quickly following internalisation and recruited more Gal9-mCherry molecules per payload molecule (Figure 5a,b). Together, these observations suggest that early rupture events, which are associated with more widespread endosomal disruption, yield greater payload escape (Fig Figure 5b).

Figure 5: Identification of distinct rupture-escape phenotypes. (a) Movie stills of endosomes containing LNP-siRNA-AF647 complexes where rupture eads to payload escape or sustained entrapment. We termed these events silencers and non-silencers, respectvely. (b) Quantification of the time from transfection to rupture for silencer and non-silencer events. (c) Quantification of the siRNA-AF647 payload to Gal9-mCherry ratio at the time of rupture, indicating that silencers are associated with more widespread endosomal disruption.

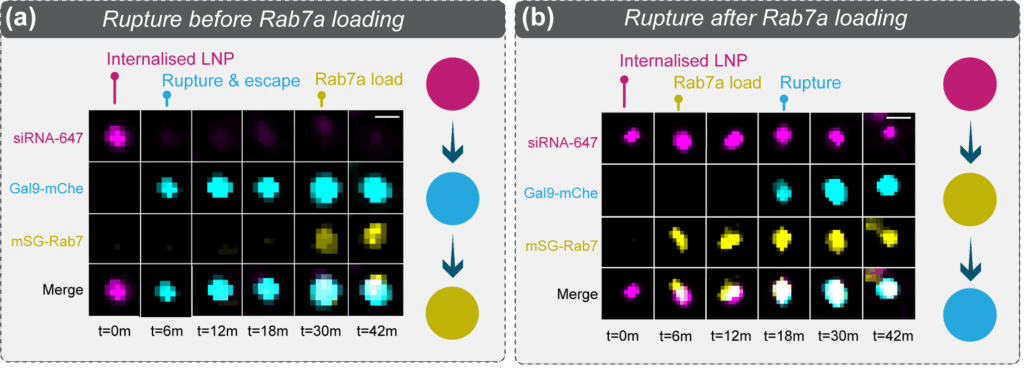

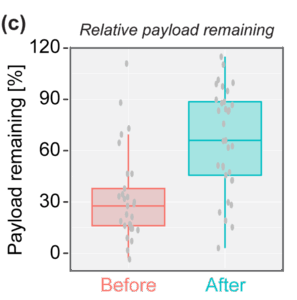

To further this idea, we asked a simple question: is payload escape more effective if the endosome ruptures before it acquires late endosome identity? In other words, is payload released more efficiently from ruptured early endosomes. We used Rab7a, a protein that specifically binds late endosomes, as a molecular clock – comparing loss of payload signal from endosomes that ruptured (localised Gal9) before Rab7a positivity with endosomes that ruptured after Rab7a positivity (Figure 6a,b). This revealed that if an endosome ruptured earlier in the pathway, before the onset of Rab7a binding, ~70% of the siRNA payload escaped into the cytosol (Figure 6c). In contrast, if the endosome ruptured after becoming a late, Rab7a positive compartment, only ~30% of the siRNA payload escaped (Figure 6c). This supports the notion that for efficient payload release, LNPs must rupture endosomes rapidly following internalisation.

Figure 6: Efficient payload escape occurs before late endosome formation. (a) Movie stills of an endosome containing a LNP-siRNA-AF647 complex undergoing rupture before maturing to a late endosome (determined by the localisation of mSG-Rab7a). Note the loss of siRNA-AF647 signal as the payload escapes into the cytosol. (b) Movie stills of an endosome containing a LNP-siRNA-AF647 complex undergoing rupture after maturing to a late endosome. Note the persistence of the siRNA-AF647 signal, indicative of payload entrapment. (c) Quantification of the siRNA-AF647 payload remaining within an endosome if rupture occured before or after Rab7a localisation, respectively. This shows that payload escape is more efficient if an endosome ruptures before it becomes a late, Rab7a positive, compartment.

Our data show that rupture events are not created equal, and that when an endosome ruptures is almost as crucial as if an endosome ruptures. Crucially, the dynamics of endosomal rupture can be programmed by LNP composition.

With these validated imaging tools, at MDC can now track rupture in real time to test if a formulation induces early, productive rupture. This capability not only clarifies fundamental aspects of LNP biology but also empowers developers to fine-tune their delivery system, helping to realise the vast promise of this therapeutic modality.

Speak to us to find out how MDC can support your drug delivery research.

Find out more about how we can help

This is the first in a series of radiopharmaceutical blogs from Dr Juliana Maynard. Juliana is an expert imaging scientist with over 20 years’ experience in nuclear medicine and translational imaging.

In this blog, Dr Phil Auckland details how MDC has established a reproducible CRISPR-Cas9 pipeline and generated new tools to better inform nanotherapeutic design

Accelerating analgesic development through human-specific in vitro systems