With the advent of personalised medicine, cancer research is not only a matter of finding drugs that kill cancer, but determining which patients are most likely to benefit from a given type of treatment.

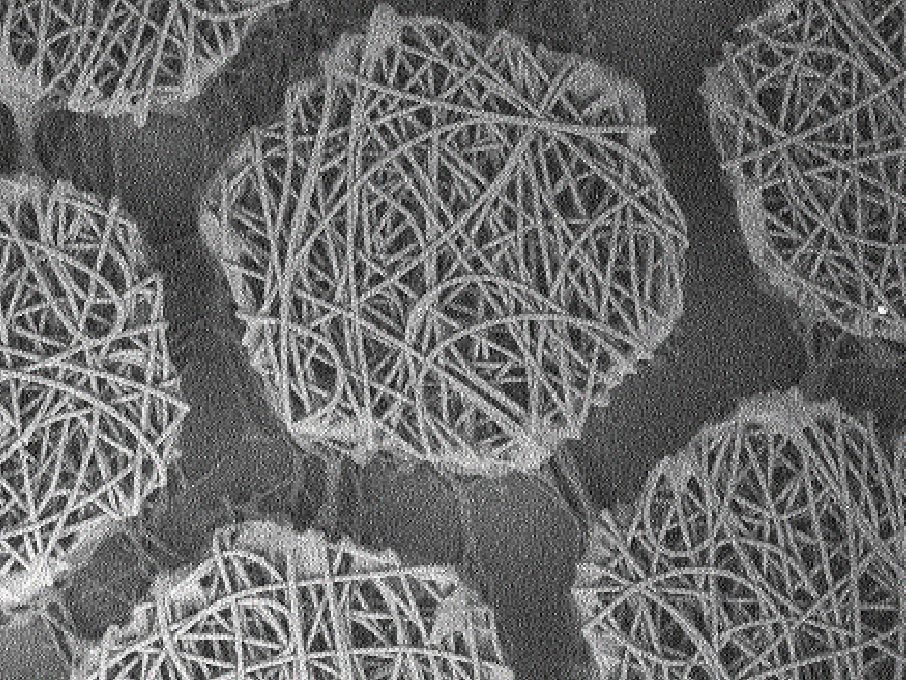

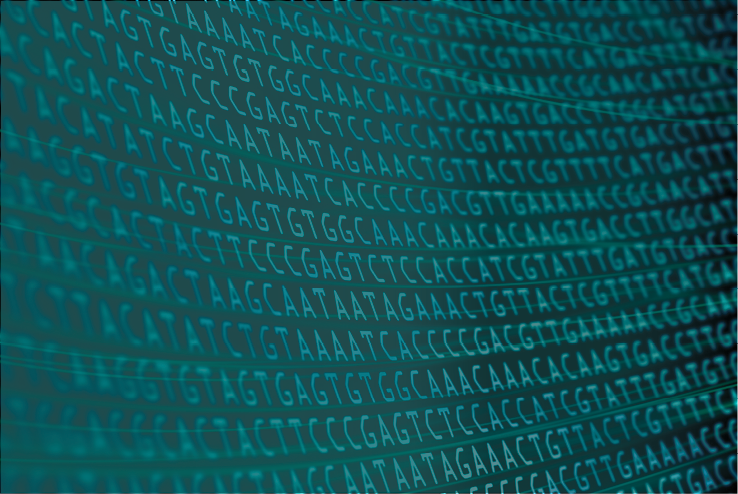

The finding that cancer cells release their DNA into the bloodstream revolutionised the way we gain insight into the cancer’s biology.

We don’t need to cut the patient open to get a biopsy and determine what’s gone wrong with the genes of the cancer cells. We can just collect some blood, analyse the DNA in it and get pretty much the same answer. This blood DNA is an excellent example of a biomarker – something that can be easily measured in the patient’s body to provide valuable information about the disease.

Blood DNA biomarkers in action: aiding decision making in prostate cancer treatment

Prostate cancer is not considered the deadliest cancer: if it’s detected early.

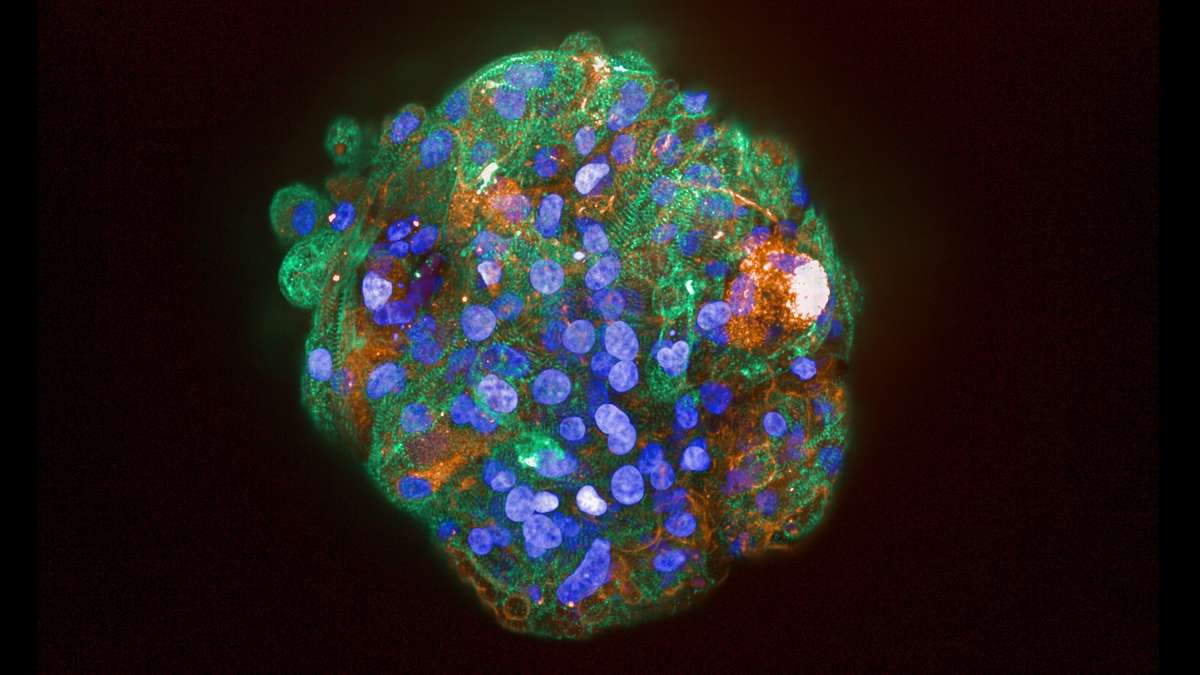

Once it metastasises, however, and becomes impossible to excise – which medical professionals call metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer, or mCRPC – the patient’s chance of survival, past two years, is only about 50%. At this stage, the available therapies for mCRPC are either taxanes or hormonal therapy. The former is a kind of chemotherapy that kills all cells that proliferate too quickly; the latter limits the synthesis and efficiency of testosterone, which often drives the prostate cancer growth.

Which one of these two therapies will work better? Which one will give the patient more time? Can we tell? According to a new study, published by a collaboration of researchers from Spain, the UK and Italy – now we can.

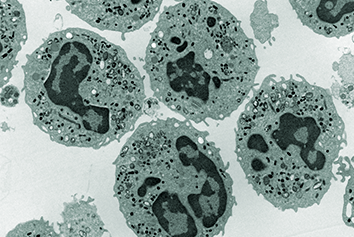

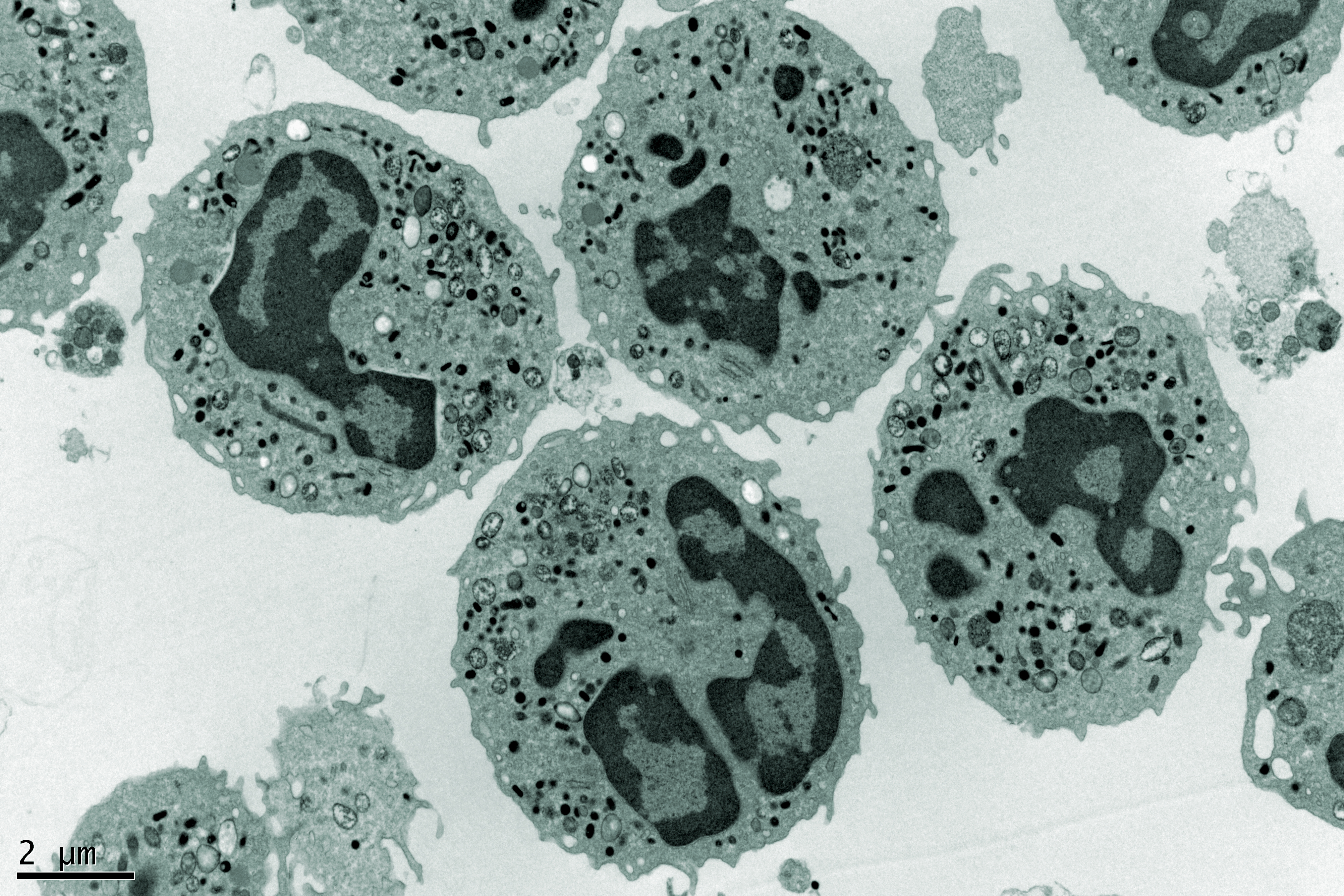

The team studied DNA in the blood of mCRPC patients. The biomarker they focused on was the number of copies of the androgen receptor (AR) gene. The protein product of the AR gene is an important part of the cancer molecular machinery that makes the cancer grow in response to testosterone.

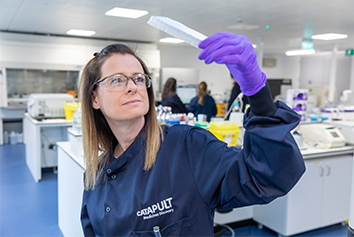

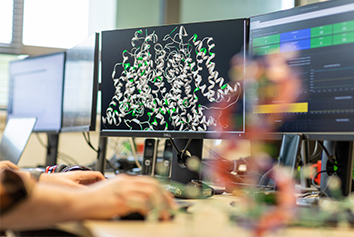

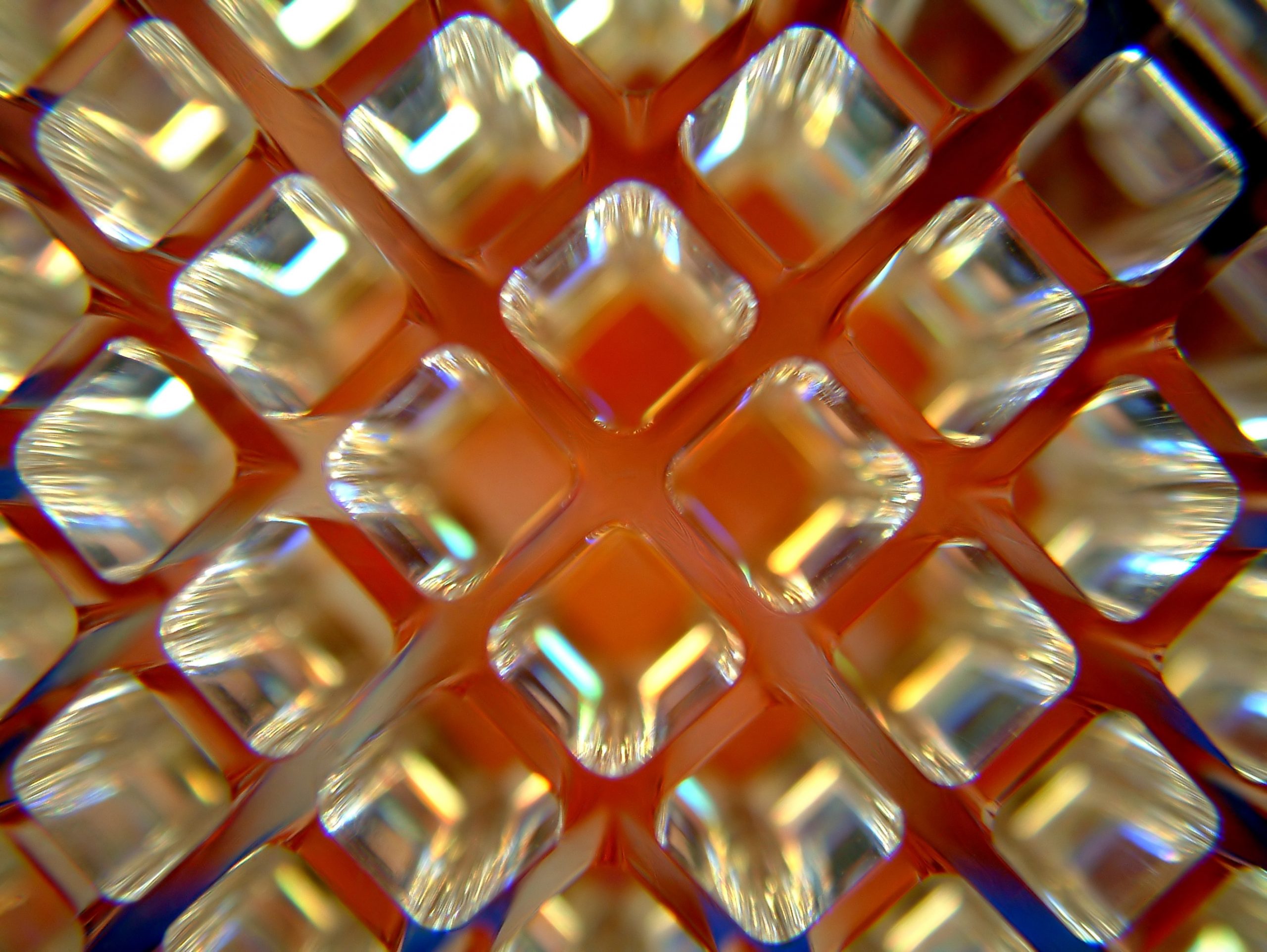

To check if the AR gene copy number in the cancer cells was normal or elevated, they needed a method that, when it comes to detecting and enumerating specific fragments of DNA, is incredibly sensitive and precise. They conducted their analyses using the droplet digital Polymerase Chain Reaction – or ddPCR – a platform that Medicines Discovery Catapult offers to its collaborators. ddPCR meets both the criteria of sensitivity and precision. It is dramatically cheaper, simpler and faster to perform compared to some other blood DNA analysis methods, such as next-generation sequencing.

The authors found that mCRPC patients with normal copy numbers of the AR gene did much better when treated with hormonal therapy, while those with increased AR levels lived longer when subjected to taxane therapy.

The future of blood DNA biomarkers

This is the first study to show that patients with elevated AR levels fare better when treated with chemotherapy, rather than hormonal therapy, and another study in an ever-growing list of publications, demonstrating the immense value of analysis of blood DNA as a biomarker.

Many of these studies also use ddPCR, because of its sensitivity, precision, low cost and swiftness from sample to answer. DNA can be isolated from blood in a matter of hours and analysed by ddPCR in less than a day. Every day is precious when deciding how best to treat a patient and this may offer a few more months, or even a few more years, for patients to spend with their loved ones.

About the author

Andrzej Rutkowski, MSc, PhD, is a Senior Scientist in the Biomarker group at Medicines Discovery Catapult.

In his career as an academic, he worked in a variety of fields, such as angiogenesis, adult stem cells, oncofetal antigens and herpes virus molecular biology. After volunteering in a diagnostic lab, he decided to move away from basic science and focus on research that can produce much more direct benefits to the patients. He transitioned to industry to support the development of drugs and diagnostic technologies focusing on biomarkers – including genetic biomarkers of cancer.