How to get your molecule into humans

Understanding the main reasons for delay and maximising the opportunities available to improve the efficiency of the transition to first-in-man clinical trials are paramount to the success of a drug development programme.

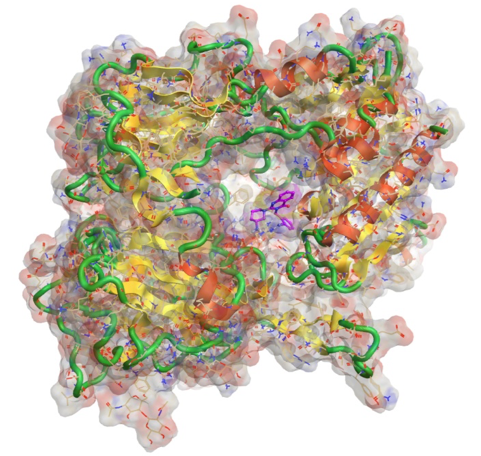

The ultimate aim for a non-clinical program is to ensure the safety of the clinical trial subjects but, to improve the efficiency of drug development, we should seek opportunities to achieve this better, cheaper and faster, whilst utilising as little active pharmaceutical ingredient as possible. Elements that should be considered are a full risk:benefit assessment focusing on what is required and when to progress the compound to clinical trials but de-risking will take longer and cost more. Appropriately designed lead optimisation studies combined with an early focus on the non-clinical strategy can save time and unnecessary expense.

When developing the non-clinical strategy, there are a number of elements to consider – the duration of dosing, daily or cyclical dosing, recovery periods, the choice of relevant rodent and non-rodent species. Strategy should be based on science and regulatory understanding. Regulatory advice, or advice from experienced CROs will help support the strategy. The extent of testing required will depend on the nature of the pharmaceutical development and design of the proposed clinical trial.

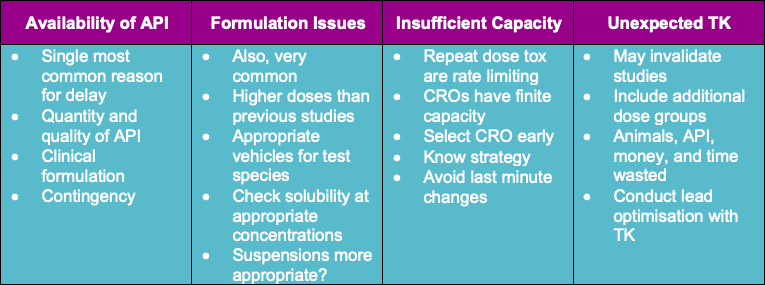

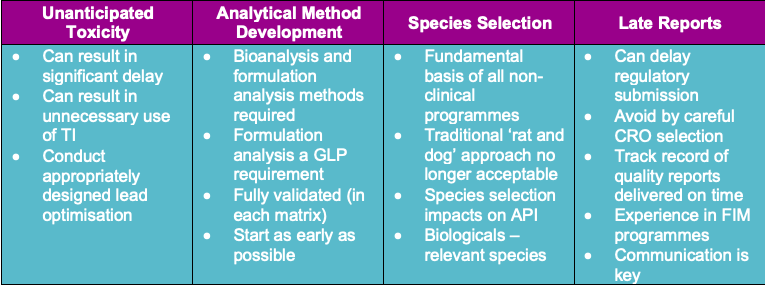

To enhance efficiency, the common reasons for delay should be considered and avoided in the strategy. The most common reasons for delay are shown in the graphic below.

Steps to enhance non-clinical efficiency opportunities include a mutual agreement CDA with the CRO, a good relationship/partnership with the CRO, integrating the CRO as part of the project team, and using the CRO for advice and guidance on the programme design. The key to a successful programme is good communication.

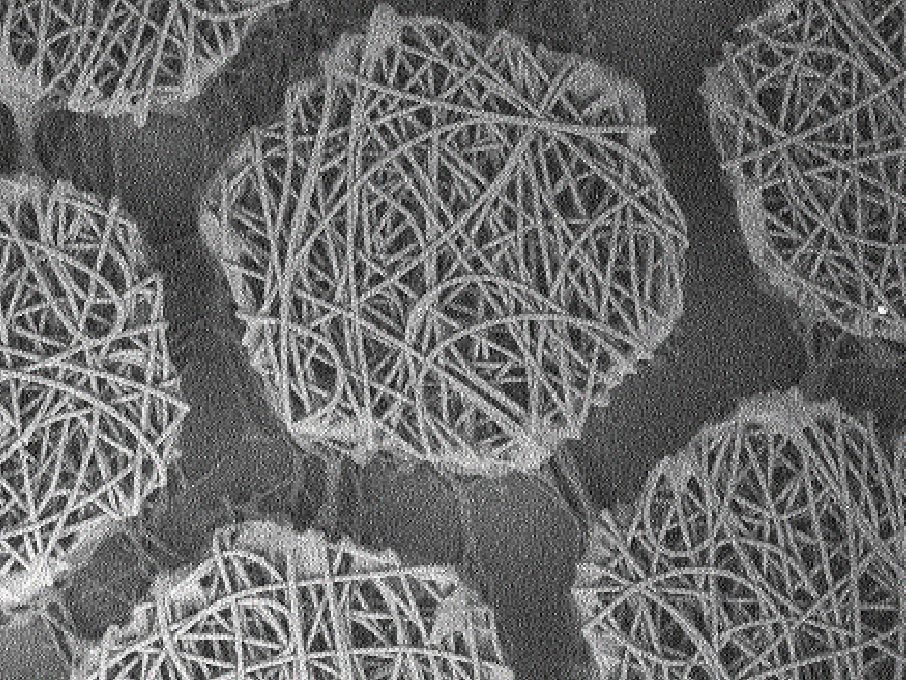

To maximise the value of toxicology studies, integrating additional measurements can help e.g. genotoxicology endpoints can be added to pivotal repeat dose rodent toxicity studies using flow cytometry analysis of micronuclei, which can reduce animal usage and cost. Safety pharmacology can be included in repeat dose toxicity studies: non-invasive telemetry, and Irwin style observations or combining a male fertility element in the sub-chronic or chronic rodent toxicity studies.

Histopathology, the pivotal endpoint of the toxicity studies can itself be rate limiting. By processing all tissues from all animals to slides and making the slides available for evaluation when required will save time. Development of clinically relevant biomarkers alongside non-clinical studies enables a direct comparison of non-clinical data to clinical data, helping to inform on clinical design and dose level selection in the clinical trials. Micro sampling allows for more efficient science with fewer animals by reducing or removing satellite animals for toxicokinetic sampling.

What does the future hold?

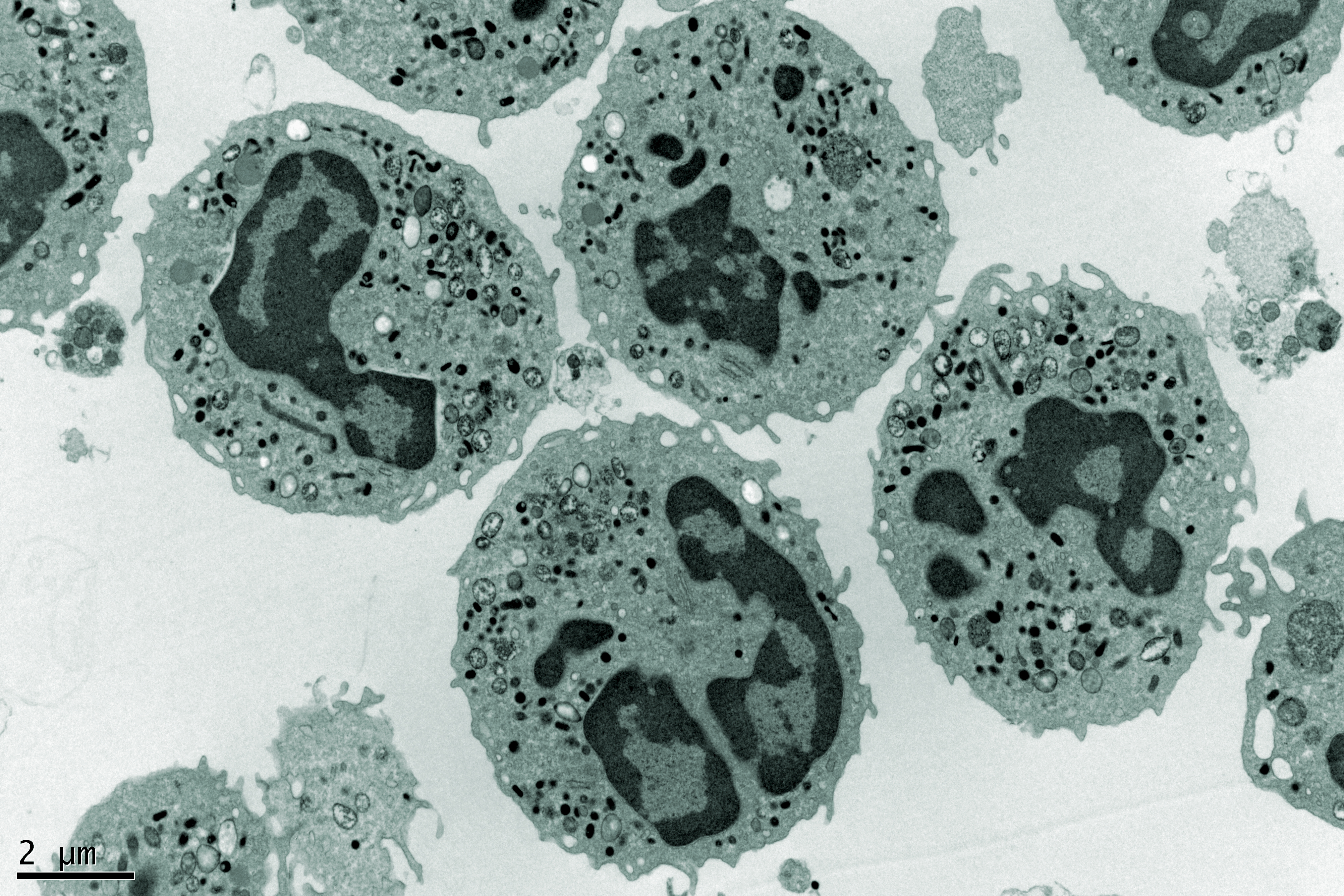

Concentrating specifically on animal models there is an increased uptake of mini pigs which have a number of advantages including similar omnivore digestion to humans, having an oestrogen cycle similar to humans, being sexually mature by six months of age, and having similar skin to humans. The mini pig offers a viable, non-rodent species as an alternative to the commonly used dog and non-human primate (NHP) models and, may provide an improved prediction of clinical efficacy.

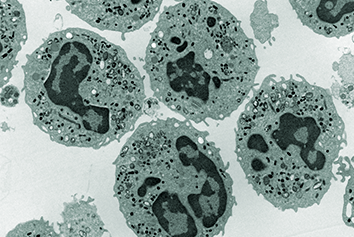

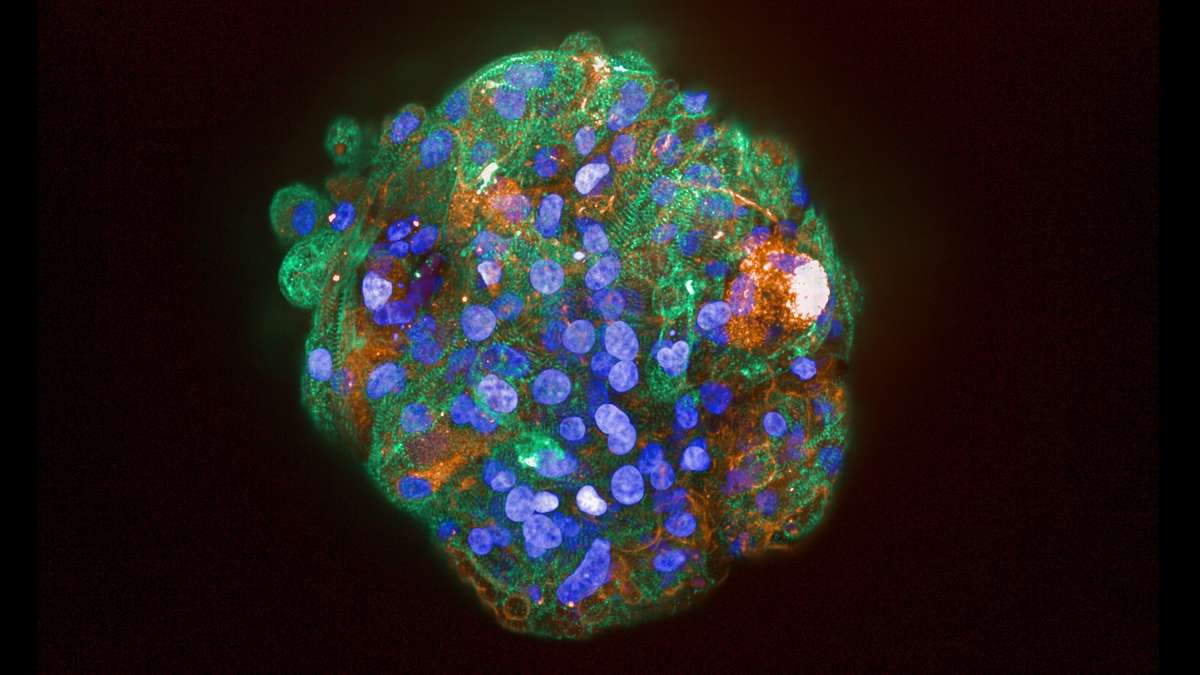

Disease models (usually mice) can be of value in providing a safety assessment in the context of the disease and, in some cases, may demonstrate toxicological responses more representative of the response in patients. Humanised transgenic animal models can be used for toxicology studies to produce better read-outs but these humanised models are very expensive. Uptake of different models could result in a concomitant reduction in the use of NHPs and dogs, which has ethical and economic benefits.

In summary there are significant opportunities to save time and money during the implementation of the non-clinical programme but retaining quality is paramount. The non-clinical strategy must be defined and a good partnership with an experienced and flexible CRO is essential to improve efficiency.

This article is based on Pauline’s talk from the MDC Connects webinar series. Watch the session Pauline took part in – Is my Compound Safe?:

About the author

Pauline Garner started her career in non-clinical 23 years ago working in the Genetic Toxicology department at Sequani as a Study Director and latterly managing the team. Then in 2012, she made the transition to the Business Development department at Sequani. In her current role as a Programme Manager, Pauline manages the programmes of work that are placed at Sequani, encompassing General, Reproductive, Juvenile and Genetic Toxicology, as well as all supporting scientific disciplines such as Analytical Chemistry, Bioanalysis, Clinical Pathology and Pathology. Sequani Limited is a Contract Research Organisation in Ledbury offering non-clinical expertise and support throughout the development of a pharmaceutical, crop protection product or chemical.