What factors encourage patients to donate clinical samples and data for research?

I think there are several factors that encourage patients to donate samples. Data is a slightly separate issue, but together they come down to the three things we already know from surveys about why patients participate in research:

Firstly we want to benefit other patients in the future. That’s always the prime driver, altruism.

Second is the hope that somebody might discover something that helps us. That might perhaps be more of a far-reached hope if you have a life-threatening illness, rather than if you have something that you’re going to have for 20, 30 or 40 years. But in this day and age the latter is a realistic hope, because the speed of science is moving so quickly.

Third is the thought at the back of our minds that if we help contribute to research in this way, if we provide samples or data, it does help train doctors and researchers in how to do research. It helps the research community. No one would ever put it like that, but I think the thought is at the back of our minds; it helps the health service somehow, in some way.

What do patients expect will happen once their samples and data have been donated?

Having donated samples or data to help research, the prime expectation that patients have is that it will be used. And that it will be used for medical or wider forms of health and social care research which are going to benefit other patients. That’s why we gave it, and that’s what we want it used for.

I remember growing up as a kid, with all the horror stories in the 60s and 70s of body parts and organs being stored in jam jars on distant shelves somewhere. My Mum was a nurse, and she and I were both horrified for different reasons. She was horrified that doctors had taken the samples without telling anyone; I was horrified that things had been done for the sake of research, to benefit the human race, or me as a young kid growing up as an adult, to help me when I got sick, and nobody had done anything with them.

One of the things that really upsets me, even today working as a patient advocate in health research, is when I hear about these sample collections, that have been taken with the best possible intentions years ago, and haven’t been used in donkey’s years, with people forgetting they even exist. That’s a waste of contributions from people like me.

If we make a donation, please use it!

What information do patients need, and in what formats, to give informed consent?

There are many discussions going on all over the place about what informed consent really is – what information patients need and how they need it. I suspect as any teacher knows, you have to find different ways of giving information to different people in the right way at the right time, for that individual to understand.

There is no one size that fits all, there is no one style that fits everyone. Some of us like papers that we can take home and read at leisure, some of us like DVDs, some of us like going online and doing interactive activities. There are all sorts of different ways. I don’t think there is a right or wrong answer. There are certain templates which have been designed by patients to explain things, and if patients have helped design it, that’s a step forward.

Personally though, for donating data, and for donating tissue especially, I would move away from consent – I’d move towards instruction. I would have a sheet of paper, or some other format – a DVD or online or whatever it is – where we patients, having made a donation, instruct people on how it should be used for ethically approved medical research. Not consenting, but actually telling them:

“I’ve made this donation to benefit humanity, you lot out there, you’re working to benefit humanity – use my legacy, use my donation!”

Are there different views held by patients and patient groups on donating samples for academic and commercial use?

One of the other challenges we face is that there are different views held by different patients. And there are different views held by different patients about academic research, about commercial research, about chronic conditions, and about acute conditions – is it threatening your life? Or is it threatening your quality of life? – and so there are differences.

There are also huge cultural differences, there are national differences across Europe. Without wishing to make a political statement – it always surprises me that patient groups across Europe ever agree on anything, never mind the national governments – there is a real challenge trying to find agreement.

Coming back to academic and commercial, though, I think there is increasing blurring between them. We live in the United Kingdom now where commercial activity in the health service is routine – whether you call it privatisation or not. Any patient that has a sample taken for diagnosis will probably find that their sample is sent off to a private laboratory, a commercial laboratory, because that’s how pathology services are run now.

We will all, if we have cancer, sooner or later have some part of our cancer pathway that comes across a commercial aspect. Clinical trials can be run in the NHS, but they are testing one drug against another drug – some drug company is eventually going to make a profit out of that – because that’s a commercial product.

I think there is a blurring of the edges. The key to me is not about academic or commercial – it is making sure that it is legitimate, ethically approved medical research. The concern that we patients have, therefore, is not about academic or commercial as such, it’s about who else is going to get hold of the data. It’s about who else might be trying things out with our tissue that we don’t know about, and what controls are put in place to stop that – whether it’s academic or commercial.

That’s the key – it’s what’s it being used for, then who is using it.

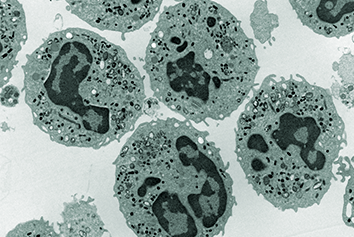

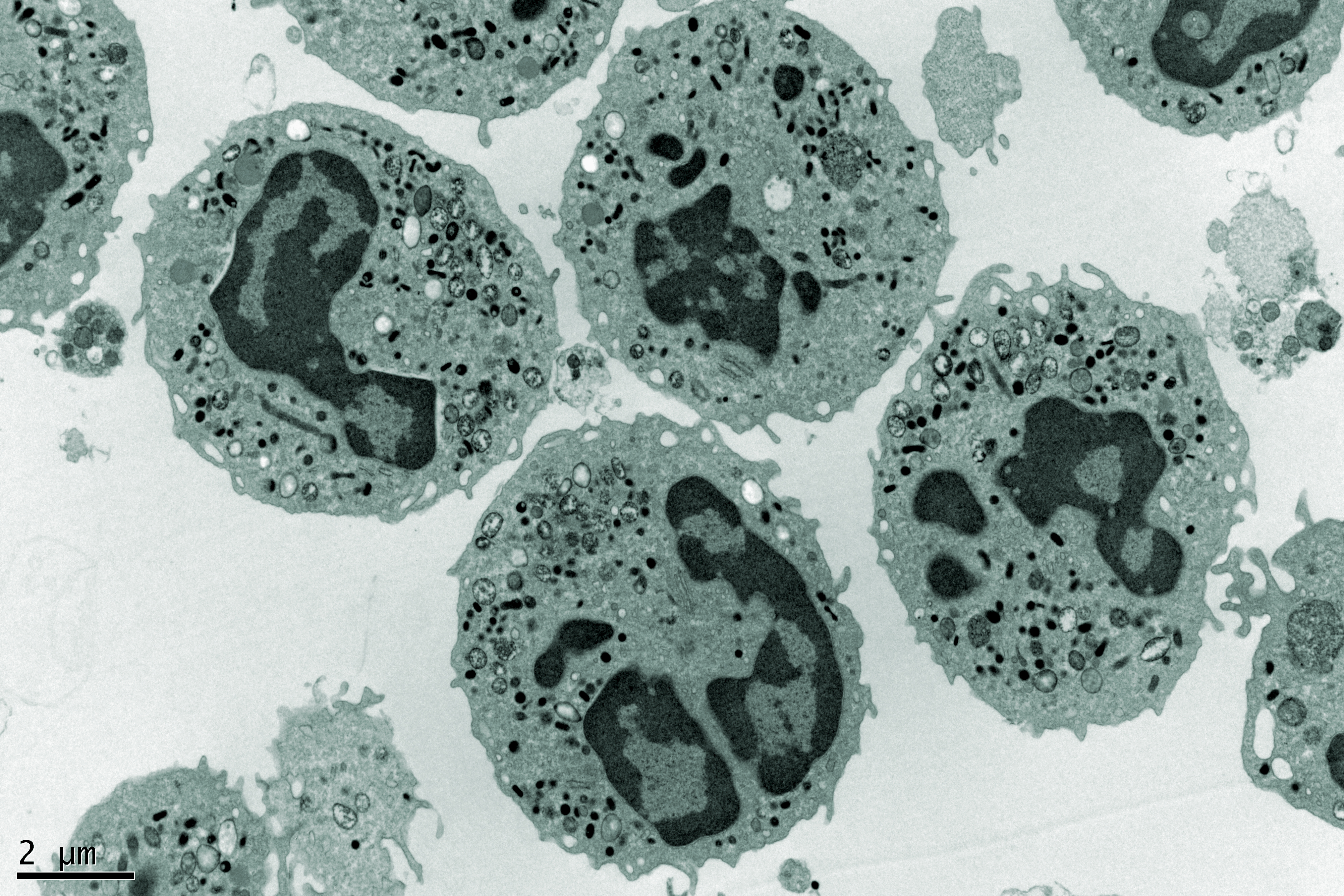

And the additional tricky point on top of all of that is this issue. Once we donate tissue samples, once we donate data, we have no clear idea what lines of research will be coming up in 5, 10, or 15 years’ time. We’ve only just started to explore the human genome and genetic predispositions to certain conditions. We’ve only just really got into molecular pathways at the level of the human cell, and we’re only just getting into things like long-term survivorship in diseases that used to kill people pretty quickly.

There are whole new aspects coming out. We don’t know what technology will bring in terms of how we can keep the human body going, physically. We don’t know what technology will do in terms of how we scan and diagnose things. So, we don’t know what the research will be in 10 years and how will they actually say:

“Well, that piece of research is going to have medical or health research benefits – we’re just doing a sort of fishing expedition, with large pools of data.”

There is that issue of how do you protect patients, and our perfectly legitimate concerns.

I’ve just raised the question; I’ve got no answer. I don’t know!

If technological advances mean new opportunities to use donated samples and data become available, what would patients want to know?

I think one approach to that particular issue – about patients not really knowing what research is going to be in 10 years time, and indeed researchers not knowing – is that if there could be some sort of line of sight on the consent form, or better still on the instruction form that patients give to researchers, about where it’s likely to to go and the kind of things that are likely to come up.

Most patients these days are aware of the possibilities of genetic research, even if we don’t understand the details. We are aware that all sorts of robot devices can now be implanted in the human body to do fabulous things, and if we’re not aware of the reality, we’ve certainly seen it in science fiction, and we know that reality catches up with science fiction quite quickly.

If there could just be “this research may include”, “this research is likely to involve” no one can ever hold anybody to that but it would be nice to know the kind of things – but always with that reassurance, “when this research does happen it will be ethically approved”, or “it will be controlled by whatever regulators are in place at the time”. And that’s something else we can’t guarantee – who regulates what?

What are the changes you’d like to see happen in the use of consented patient samples and data?

Over and above some of the things I’ve suggested already, the biggest single change I would like to see in this area about using patient tissue and using patient data is giving patients more say in who gets access to the tissue and the data – and what for.

There are some excellent examples already available in the 100,000 Genome project for example, run by Genomics England in the UK. You have patients, not just patients but participants – people whose genomes have been sequenced – and they sit on the data access review committee. So the people whose data and genomes are going to be used for research get to see who’s doing it, what they want to do with it and they get the chance to say no.

Usually of course, they say yes because they can see what the purposes are, and who’s doing it, and the fact that it’s all legitimate, ethically-approved, controlled, whatever. But put some patient representatives on committees!

I don’t know how many academic tissue research collections have already got patients sitting on their data review or release committees. I suspect it’s very few. One of the other things I’d like to see to try to resolve this problem is letting people know about the data around it. So, “what was the patient suffering from?”, “what treatment had they had?”, “how was the data collected?”, “how’s the tissue been collected?”, “how’s it been stored?” – that kind of stuff.

I would like to see far more comprehensive registers or catalogues of who’s got all this stuff and someone, somewhere – and it would probably be a commercial entity – helping put people in touch. Because that again that comes back to why we patients donate the stuff; it’s so that it can be used to benefit humanity.

So, let’s get on and do it – and do it a bit more quickly!

This post is based on an interview with Richard Stephens. The video of that interview is below. Unfortunately, there were technical issues with the sound – as a result we’ve provided subtitles on the video, and the above write-up is based on a slightly edited transcript.

About the author

Richard Stephens is a survivor of two cancers, a heart emergency, multiple morbidities and late effects. He has participated in four interventional studies and nine others.

Richard was the patient representative on the Independent Cancer Taskforce that produced the English National Cancer Strategy. He Chairs the NCRI’s Consumer Forum and has roles with NIHR, NHS England, PHE-NCRAS, CQC, MRC CTU, Genomics England, Cancer Research UK, ABPI, BBMRI-ERIC and more.

Richard is a founder member of the AllTrials and useMYdata movements, and the founding Co-Editor-in-Chief of Research Involvement and Engagement, the world’s first (and only) academic journal to cover involving or engaging patients, caregivers and the public as partners in health and social care research.

All the above roles are voluntary, with some remunerated via honoraria. Richard has also worked with life science companies as an NCRI Consumer, and with Pfizer and AstraZeneca as a contracted advisor.